Particle System

|

|

I recently started to explore particle system. It is surprising that it only requires high school knowledge in physics to build up such a tool. Particle system can be used as a form-finding tool for designing a hanging chain model or cable nets structure that Frei Otto and Antoni Gaudi similar did in their physical experimentation in order to have structures in pure tension or compression. This post will look into the process step by step. By the end of this post, you will be seeing a simple physic engine built within Rhino/Grasshopper environment in C# programming language. It is recommended to have an intermidate level of C# programming and knowledge of object-oriented programming.

In fact, there are already existing physic engines available for Grasshopper users, such as Kangaroo, Flexhopper, or PhysX.GH. The idea is not taking available tools for granted, it is important to understand its logic and use it consciously. The aim of this post is trying to reveal the underlying principle of physic engines by explaining it in a particle system.

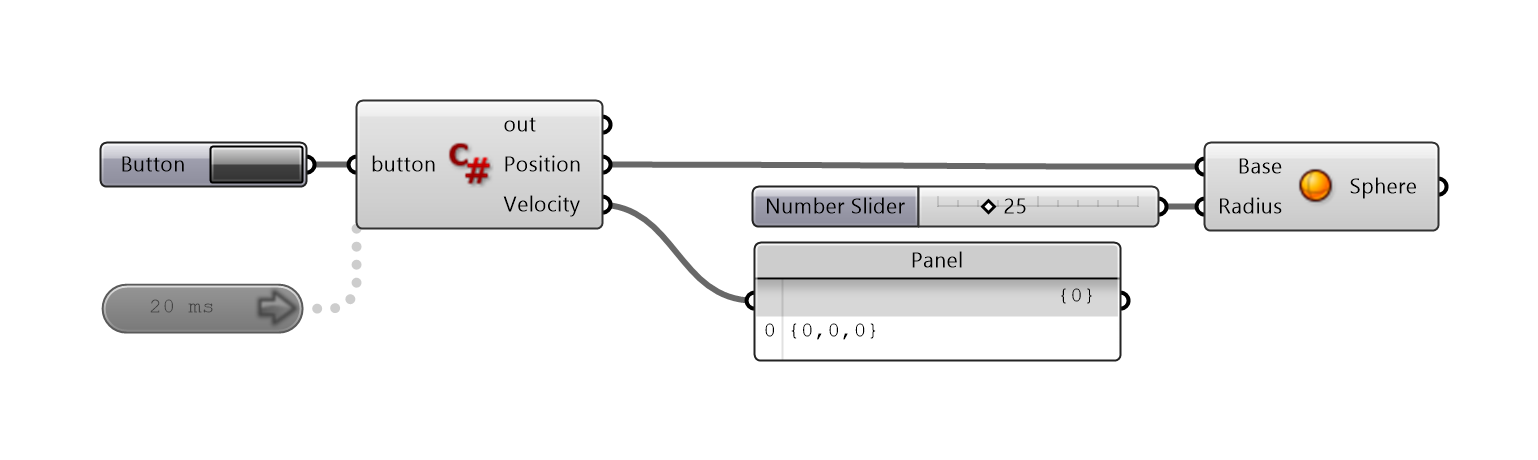

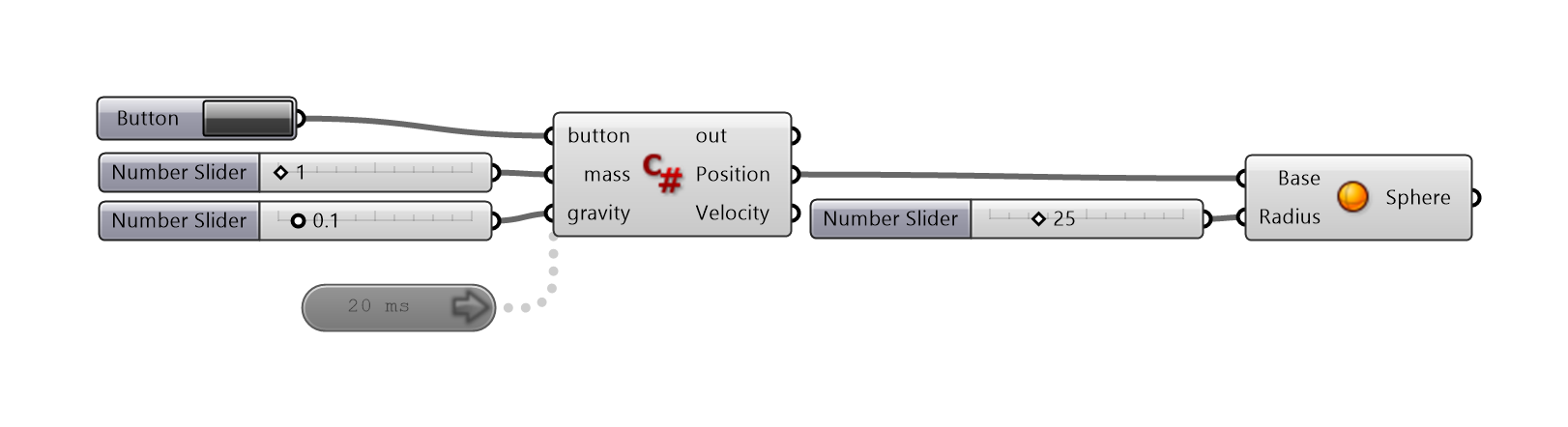

C# Component Setup

The main scripting will take place in a C# scripting component. We will first set up our component and understand how the data is stored and processed. The initial input is a boolean button to reset the computational process and a timer attached at the bottom of the component to update the process in a certain time interval. You can right-click the timer to select your desired interval. The outputs will be the current position and velocity of the particle. Remember to keep the timer disabled if you are not using it, otherwise, the C# script component will be running indefinitely in the background and consume your computer’s memory heavily.

The main scripting will take place in a C# scripting component. We will first set up our component and understand how the data is stored and processed. The initial input is a boolean button to reset the computational process and a timer attached at the bottom of the component to update the process in a certain time interval. You can right-click the timer to select your desired interval. The outputs will be the current position and velocity of the particle. Remember to keep the timer disabled if you are not using it, otherwise, the C# script component will be running indefinitely in the background and consume your computer’s memory heavily.

We can open up the C# scripting editor by double-clicking the C# scripting component. The run script area is where the script will be executed. We set a condition to reset the process if we click the reset button and the output ports will extract the current particle information from the global scope area. The global scope is where we store particle’s attributes as persistent data which the states of the particle are stored in every execution so we will be able to view the intermediate changes in run time.

Particle

Particle can be described as a localised object. Each particle has its own set of attributes, such as position, velocity, mass, and other information that might be useful to attach with it. These attributes, however, are all dimensionless, we can of course logically assign certain units on it, but what we actually care about is its kinematic movement. In other words, how particles move in a given environment.

Particle can be described as a localised object. Each particle has its own set of attributes, such as position, velocity, mass, and other information that might be useful to attach with it. These attributes, however, are all dimensionless, we can of course logically assign certain units on it, but what we actually care about is its kinematic movement. In other words, how particles move in a given environment.

Falling ball simulation

Particle is moved toward a direction by a given or a set of force acts on it. We will start by simulating a single particle or a falling ball and observe how the particle responds to its own weight. Gravity, in this case, will be the only force that act on the ball. To calculate the force acts on the ball by gravity, we will borrow Newton’s laws of motion (Force = mass * acceleration).

private void RunScript(bool button, double mass, double gravity, ref object Position, ref object Velocity)

{

if(button)

{

pt = Point3d.Origin;

velocity = Vector3d.Zero;

}

else

{

Tuple<Point3d, Vector3d> compute = fall(pt, mass, gravity, velocity);

pt += compute.Item1;

velocity += compute.Item2;

}

Position = pt;

Velocity = velocity;

}

// <Custom additional code>

Point3d pt = new Point3d(0, 0, 0);

Vector3d velocity = new Vector3d(0, 0, 0);

Tuple<Point3d, Vector3d> fall (Point3d pt, double mass, double gravity, Vector3d velocity)

{

double forceZ = mass * gravity; // newton's law

Vector3d accelerationZ = new Vector3d(0, 0, -forceZ / mass); // calculate the acceleration of the particle, forceZ is inverted

Vector3d velocity_current = (velocity + accelerationZ); // update velocity

Point3d pt_position = pt + velocity; // update position

return Tuple.Create(pt_position, velocity_current);

}

// <Custom additional code>

That’s it! We have made our very first physic engine! To make the ball falling downward in our coordinate system, the force Z is therefore inverted at the line where we calculate the acceleration. Now let’s take one step further by adding a bit of complexity for a spring simulation.

Single Spring Simulation

Single spring simulation has two additional forces compared to our previous falling ball simulation:

-

Spring Force (Force = Spring Constant * Δ L(Length - Rest Length)):

It is widely known as Hooke’s Law that a force is exerted if an elastic spring is compressed or extended in relation to its rest length. Rest length means the length of spring in a state of equilibrium without any force exerted on it. The value of the spring constant represents the stiffness of the spring which can be a reasonable arbitrary non-zero value for our simulation. -

Damping Force (Force = Damping Constant * Particle’s Velocity):

The damping force always remains opposite to particle’s motion directoin. It is the force to slow down particle’s motion by associating with particle’s velocity. One can imagine a ping pong ball falling vertically on a table, the ping pong ball won’t bounce back as high as the position it was released as it loses certain energy when it contacts the table. Without the damping force, our system will not reach equilibrium, the dynamic particle will keep bouncing forth and back indefinitely. You can try to set the damping constant to 0 to see the non-stop bouncing motion. Similar to the spring constant, the damping constant is an arbitrary non-zero value.

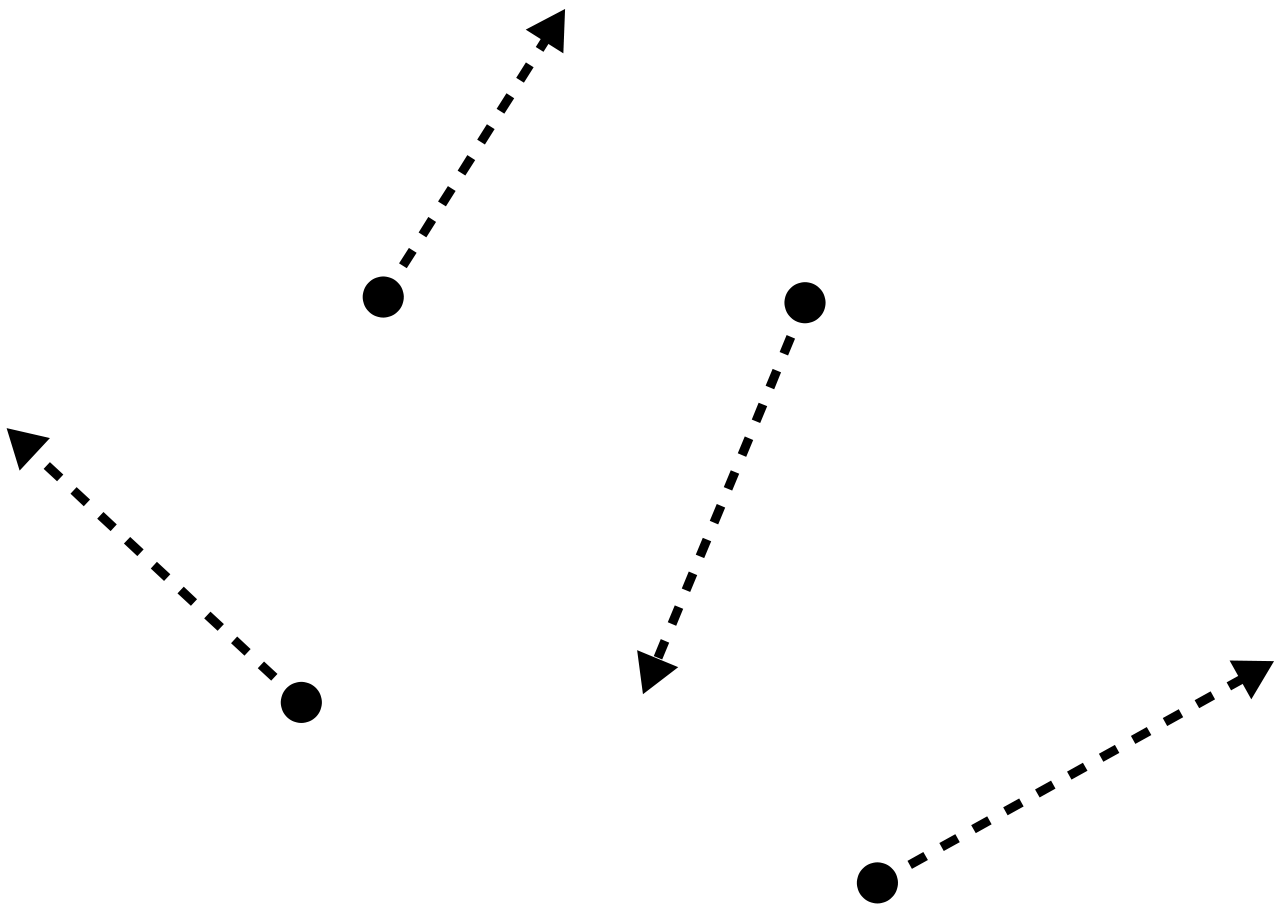

In addition, we will add one more particle(particle 1) at the origin as our anchoring point which remains constantly static without being affected by any forces. Particle 2 will be the falling ball particle with a spring connected to particle 1. Below is a force diagram that illustrates how three forces interact with each other.

private void RunScript(bool button, double mass, double gravity, double spring, double damping, Point3d anchorPt, Point3d StartingPt, ref object Position, ref object Velocity)

{

if(button)

{

pt = StartingPt;

velocity = Vector3d.Zero;

}

else

{

Tuple<Point3d, Vector3d> compute = physic_engine(pt, mass, gravity, velocity, damping, anchorPt, spring);

pt = compute.Item1;

velocity = compute.Item2;

}

Position = pt;

Velocity = velocity;

}

// <Custom additional code>

Point3d pt = new Point3d(0, 0, 0);

Vector3d velocity = new Vector3d(0, 0, 0);

Tuple<Point3d, Vector3d> physic_engine (Point3d pt, double mass, double gravity, Vector3d velocity, double damping, Point3d anchorPt, double spring)

{

double forceSpring_Z = -spring * (pt.Z - anchorPt.Z);

double forceSpring_Y = -spring * (pt.Y - anchorPt.Y);

double forceSpring_X = -spring * (pt.X - anchorPt.X);

double forceDamping_Z = damping * velocity.Z;

double forceDamping_Y = damping * velocity.Y;

double forceDamping_X = damping * velocity.X;

double forceGravity = mass * -gravity;

double forceZ = forceSpring_Z - forceDamping_Z + forceGravity ;

double forceY = forceSpring_Y - forceDamping_Y;

double forceX = forceSpring_X - forceDamping_X;

Vector3d acceleration = new Vector3d(forceX / mass, forceY / mass, forceZ / mass);

Vector3d velocity_current = (velocity + acceleration);

Point3d pt_current = pt + velocity_current;

return Tuple.Create(pt_current, velocity_current);

}

// </Custom additional code>

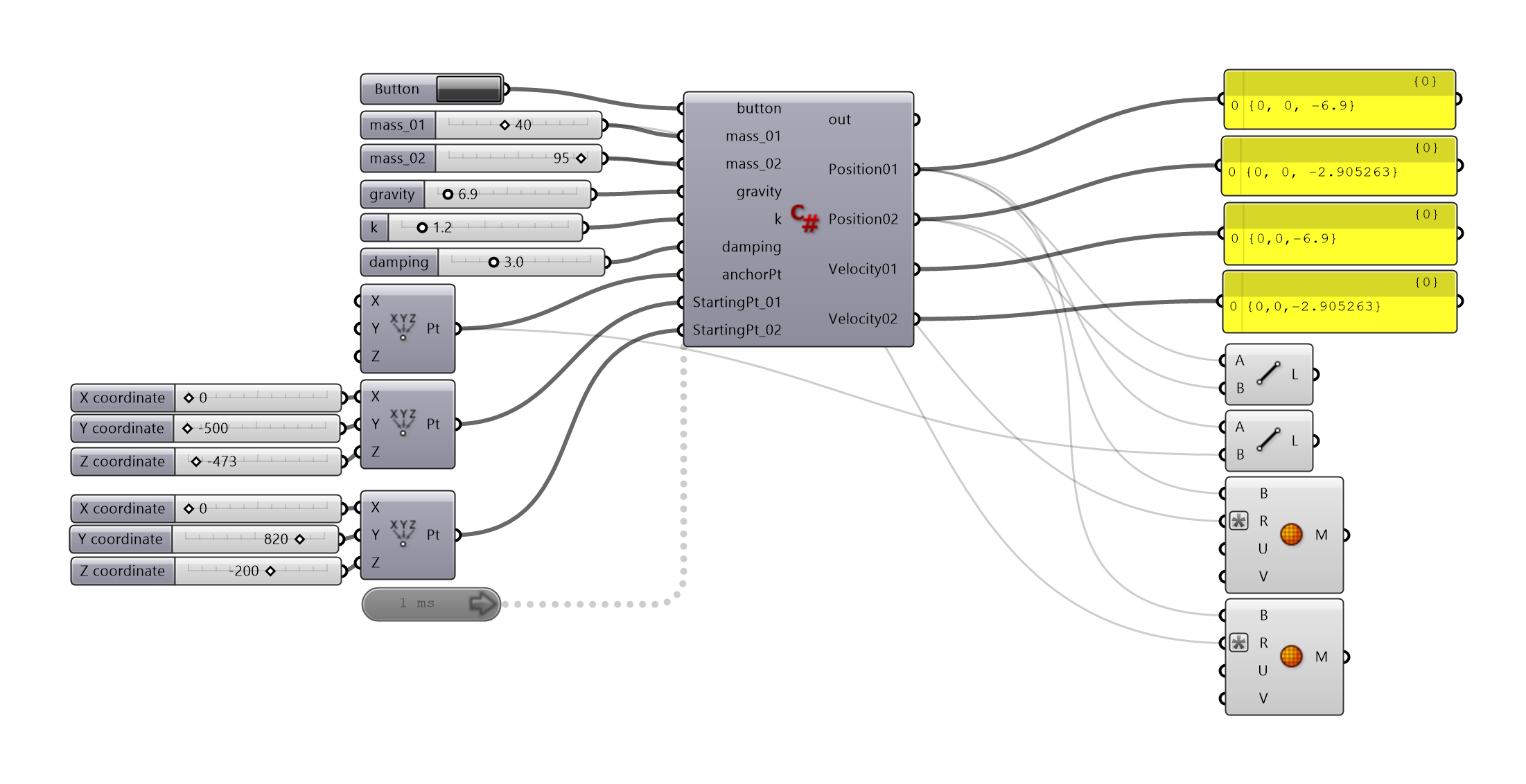

Two Springs Simulation

Next step we will add one additional dynamic particle(particle 3) with a spring connected to particle 2. We will first examine the force diagram to see what forces act on each dynamic particles and formulate the force structure accordingly.

We first look at the force diagram for particle 2 of which has one gravity force from its own weight and a pair of spring force, damping force that are associated with the static particle 1. In addition, a newly created particle 3 is connected with a spring below particle 2 which exerts one additional pair of spring force/damping force.

It is clear now that the number of forces act on the particle is linked to the particle’s connectivity. Among the three particles in this simulation, particle 2 has 2 connectivities with the static particle 1 and a dynamic particle 3 below it. The other two particles remain simple with 1 connectivity.

Just like our previous single spring simulation, particle 3 is only associated with particle 2, so the force diagram is the same to the previous force diagram for particle 2.

private void RunScript(bool button, double mass_01, double mass_02, double gravity, double k, double damping, Point3d anchorPt, Point3d StartingPt_01, Point3d StartingPt_02, ref object Position01, ref object Position02, ref object Velocity01, ref object Velocity02)

{

if(button)

{

pt_1 = StartingPt_01;

pt_2 = StartingPt_02;

velocity_01 = Vector3d.Zero;

velocity_02 = Vector3d.Zero;

}

else

{

Tuple<Point3d, Point3d, Vector3d, Vector3d> compute = physic_engine(pt_1, pt_2, mass_01, mass_02, gravity, velocity_01, velocity_02, damping, anchorPt, k);

pt_1 = compute.Item1;

pt_2 = compute.Item2;

velocity_01 = compute.Item3;

velocity_02 = compute.Item4;

}

Position01 = pt_1;

Position02 = pt_2;

Velocity01 = velocity_01;

Velocity02 = velocity_02;

}

// <Custom additional code>

Point3d pt_1 = new Point3d(0, 0, 0);

Point3d pt_2 = new Point3d(0, 0, 0);

Vector3d velocity_01 = new Vector3d(0, 0, 0);

Vector3d velocity_02 = new Vector3d(0, 0, 0);

Tuple<Point3d, Point3d, Vector3d, Vector3d> physic_engine (Point3d pt_1, Point3d pt_2, double mass_01, double mass_02, double gravity, Vector3d velocity_01, Vector3d velocity_02, double damping, Point3d anchorPt, double k)

{

// spring force for particle 2

double forceSpring_Z_01 = -k * (pt_1.Z - anchorPt.Z);

double forceSpring_Y_01 = -k * (pt_1.Y - anchorPt.Y);

double forceSpring_X_01 = -k * (pt_1.X - anchorPt.X);

// spring force for particle 3

double forceSpring_Z_02 = -k * (pt_2.Z - pt_1.Z);

double forceSpring_Y_02 = -k * (pt_2.Y - pt_1.Y);

double forceSpring_X_02 = -k * (pt_2.X - pt_1.X);

// damping force for particle 2

double forceDamping_Z_01 = damping * velocity_01.Z;

double forceDamping_Y_01 = damping * velocity_01.Y;

double forceDamping_X_01 = damping * velocity_01.X;

// damping force for particle 3

double forceDamping_Z_02 = damping * velocity_02.Z;

double forceDamping_Y_02 = damping * velocity_02.Y;

double forceDamping_X_02 = damping * velocity_02.X;

// gravity force for particle 2

double forceGravity_01 = mass_01 * gravity;

// gravity force for particle 3

double forceGravity_02 = mass_02 * gravity;

// calculatie the individual force for particle 2

double forceZ_01 = forceSpring_Z_01 - forceDamping_Z_01 - forceSpring_Z_02 + forceDamping_Z_02 - forceGravity_01;

double forceY_01 = forceSpring_Y_01 - forceDamping_Y_01 - forceSpring_Y_02 + forceDamping_Y_02;

double forceX_01 = forceSpring_X_01 - forceDamping_X_01 - forceSpring_X_02 + forceDamping_X_02;

// calculatie the individual force for particle 3

double forceZ_02 = forceSpring_Z_02 - forceDamping_Z_02 - forceGravity_01;

double forceY_02 = forceSpring_Y_02 - forceDamping_Y_02;

double forceX_02 = forceSpring_X_02 - forceDamping_X_02;

// calculate the acceleration of particle 2

Vector3d acceleration_Z_01 = new Vector3d(forceX_01 / mass_01, forceY_01 / mass_01, forceZ_01 / mass_01);

// calculate the acceleration of particle 3

Vector3d acceleration_Z_02 = new Vector3d(forceX_02 / mass_02, forceY_02 / mass_02, forceZ_02 / mass_02);

Vector3d velocity_01_current = (velocity_01 + acceleration_Z_01);

Vector3d velocity_02_current = (velocity_02 + acceleration_Z_02);

Point3d pt_01_current = pt_1 + velocity_01_current;

Point3d pt_02_current = pt_2 + velocity_02_current;

return Tuple.Create(pt_01_current, pt_02_current, velocity_01_current, velocity_02_current);

}

The code is getting longer because we basically need to double up the formulation for the extra particle involved. It is not the best practice because if we have 10 more particles involved in the system, the code will be easily 10 times longer. To solve this issue, we will make use of Object-Oriented Programming to better maintain our code structure.

Treating Particle as Object

Earlier we mentioned every particle has its own set of attributes, which we can make use of it by establishing a Particle class that we associate these attributes with every particle we generate. In the later stage, we can easily extract this information whenever we update its position, velocity, etc. At this point, each particle has:

- Position

- Velocity

- Status: Is it static or dynamic.

- Mass

public class Particle

{

public Point3d Position;

public Vector3d Velocity;

public int Status;

public double Mass;

public Particle(Point3d initialPosition, Vector3d initialVelocity, double mass, int particleStatus)

{

Position = initialPosition;

Velocity = initialVelocity;

Status = particleStatus;

Mass = mass;

}

}

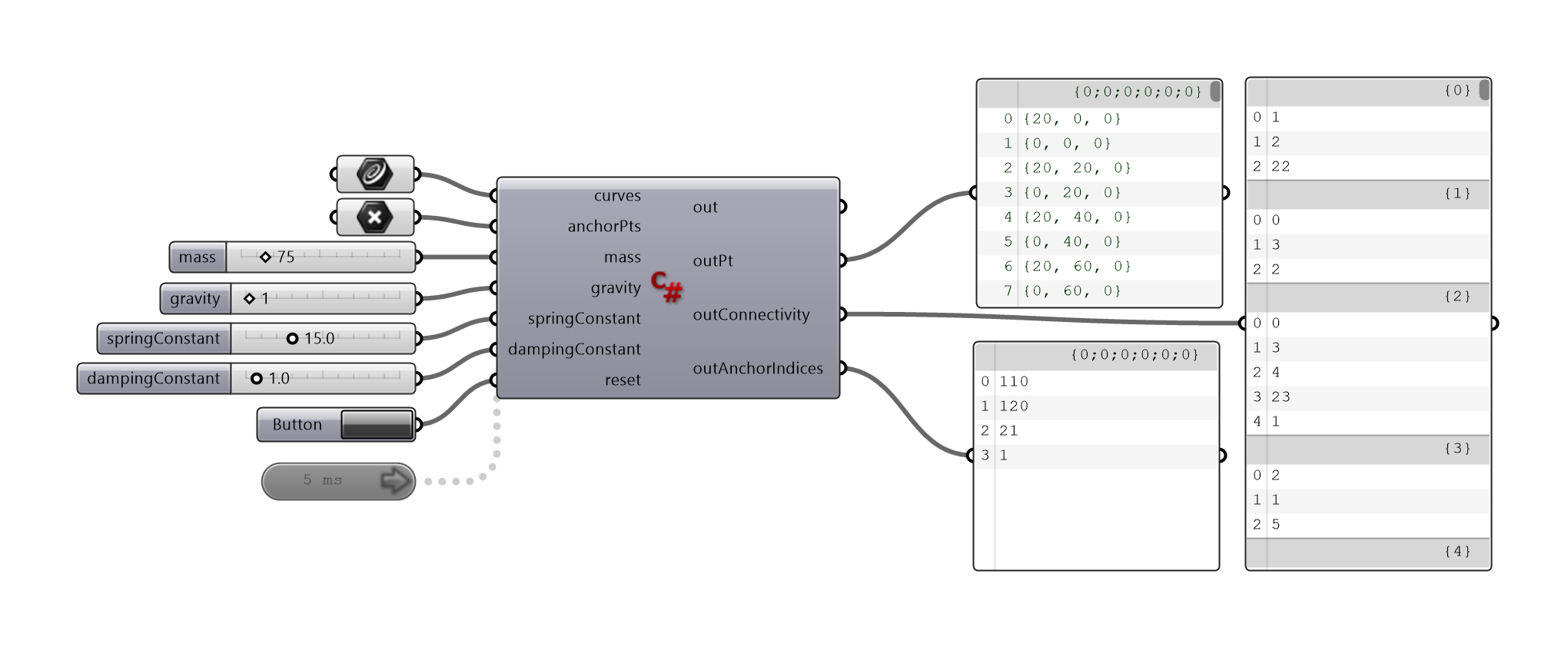

Searching Particle’s Topological Connectivity

In our two springs simulation, we can clearly see the connectivity of each particle as there are simply three particles involved in the system. To tackle more complicated connectivity such as a cable nets structure, we need a utility function to search the connectivity of each particle. The function will iterate every spring we feed in, look for the particles from the start and end point of the spring, store the particle in the particle list if they are not duplicate to the stored list, then build the connectivity data structure by the particle’s index.

Tuple<List<Point3d>, DataTree<int>> SearchConnectivity(List<Curve> curves)

{

List<Point3d> myPts = new List<Point3d>();

DataTree<int> connectivity = new DataTree<int>();

for (int i = 0; i < curves.Count; i++)

{

Point3d startPt = curves[i].PointAtStart;

Point3d endPt = curves[i].PointAtEnd;

if (myPts.Contains(startPt) && myPts.Contains(endPt))

{

connectivity.Add(myPts.IndexOf(endPt), new GH_Path(myPts.IndexOf(startPt)));

connectivity.Add(myPts.IndexOf(startPt), new GH_Path(myPts.IndexOf(endPt)));

}

else if (myPts.Contains(startPt))

{

myPts.Add(endPt);

connectivity.Add(myPts.IndexOf(endPt), new GH_Path(myPts.IndexOf(startPt)));

connectivity.Add(myPts.IndexOf(startPt), new GH_Path(myPts.IndexOf(endPt)));

}

else if (myPts.Contains(endPt))

{

myPts.Add(startPt);

connectivity.Add(myPts.IndexOf(endPt), new GH_Path(myPts.IndexOf(startPt)));

connectivity.Add(myPts.IndexOf(startPt), new GH_Path(myPts.IndexOf(endPt)));

}

else

{

myPts.Add(startPt);

myPts.Add(endPt);

connectivity.Add(myPts.IndexOf(endPt), new GH_Path(myPts.IndexOf(startPt)));

connectivity.Add(myPts.IndexOf(startPt), new GH_Path(myPts.IndexOf(endPt)));

}

}

return Tuple.Create(myPts, connectivity);

}

Searching Anchoring Indices

Each particle has a status determining either it is a static or dynamic particle. We will make an entry port at the c# scripting component to indentify anchoring points and develop a utility function to find which particles match the same coodinates of the anchoring points and return its indices.

List<int> SearchAnchorIndices(List<Point3d> nodes, List<Point3d> anchors)

{

List<int> anchorsIndices = new List<int>();

for (int i = 0; i < anchors.Count; i++)

if (nodes.Contains(anchors[i])) anchorsIndices.Add(nodes.IndexOf(anchors[i]));

return anchorsIndices;

}

Let’s go back to the main code area and update what we have developed so far.

private void RunScript(List<Curve> curves, List<Point3d> anchorPts, double mass, double gravity, double springConstant, double dampingConstant, bool reset, ref object outPt, ref object outConnectivity, ref object outAnchorIndices, ref object outPositions, ref object outVelocities, ref object outMass, ref object outStatus, ref object outLines)

{

// <Custom code>

List<Point3d> allParticles;

DataTree<int> connectivity;

Tuple<List<Point3d>, DataTree<int>> searchedConnectivity = SearchConnectivity(curves);

allParticles = searchedConnectivity.Item1;

connectivity = searchedConnectivity.Item2;

List<int> anchorsIndices;

anchorsIndices = SearchAnchorIndices(allParticles, anchorPts);

if (reset)

{

particles = allParticles;

for (int i = 0; i < particles.Count; i++) velocities.Add(Vector3d.Zero);

}

// Outputs-------------------------------------------------------

outPt = allParticles;

outConnectivity = connectivity;

outAnchorIndices = anchorsIndices;

// </Custom code>

}

// <Custom additional code>

List<Point3d> particles = new List<Point3d>();

List<Vector3d> velocities = new List<Vector3d>();

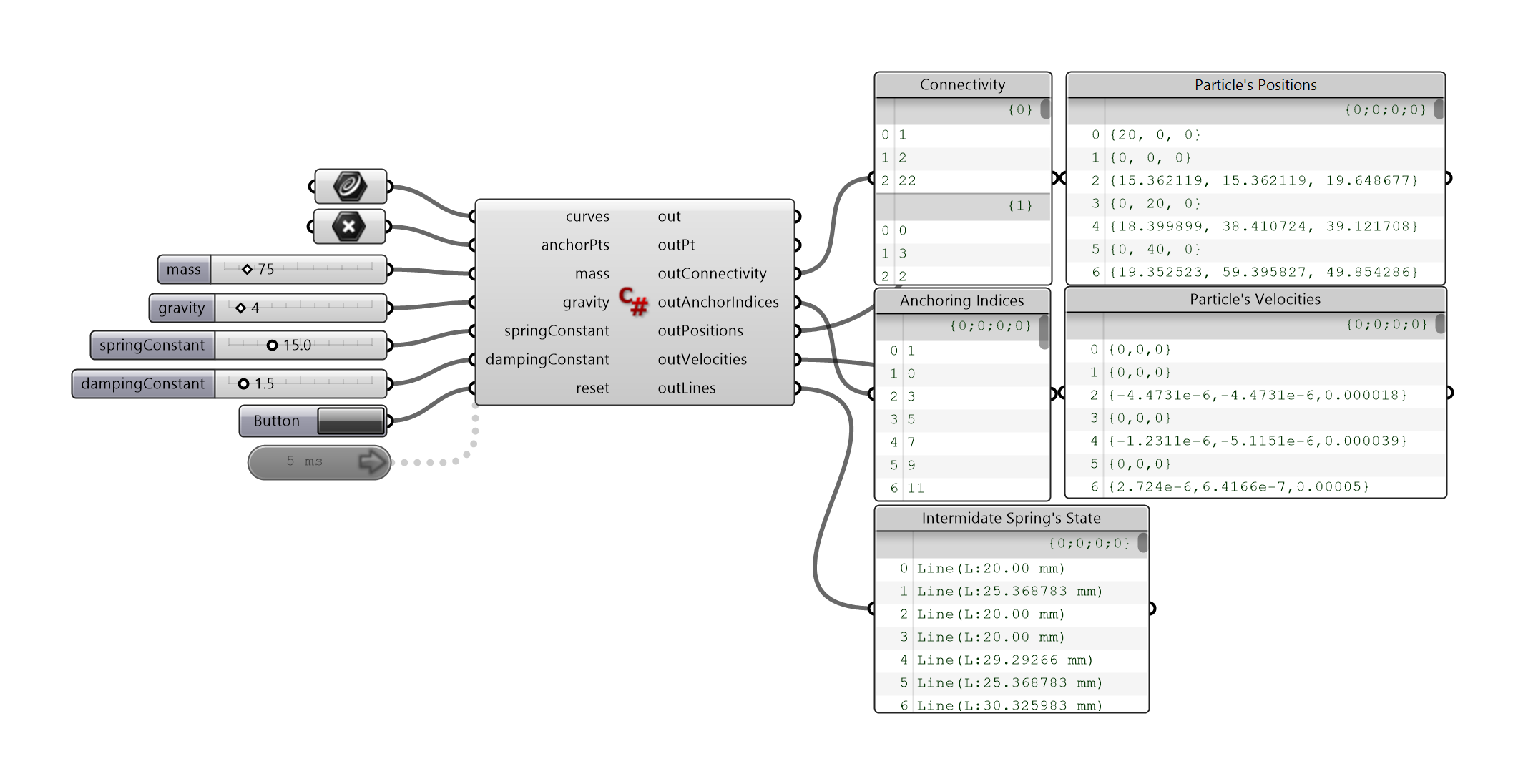

Physic Engine Class

This is where the main computation takes place. So far we have made a particle class with some attributes, but we have not instantiated it. To do so, we will make a separate class called PhysicEngineProcessor that whenever it is called, its constructor will create a list of particle objects and assign its cooresponding attributes.

public class PhysicEngineProcessor

{

List<Particle> Particles;

public double Mass;

public double Gravity;

public double SpringConstant;

public double DampingConstant;

public DataTree<int> Connectivity;

public PhysicEngineProcessor(List<Point3d> initialParticles, List<Vector3d> initialVelocities, List<int> anchorIndices, double mass, double gravity, double springConstant, double dampingConstant, DataTree<int> connectivity)

{

Particles = new List<Particle>();

Mass = mass;

Gravity = gravity;

SpringConstant = springConstant;

DampingConstant = dampingConstant;

Connectivity = connectivity;

for (int i = 0; i < initialParticles.Count; i++)

{

if (anchorIndices.Contains(i))

Particles.Add(new Particle(initialParticles[i], initialVelocities[i], Mass, 0)); // status: 0-> Static, 1-> Dynamic

else

Particles.Add(new Particle(initialParticles[i], initialVelocities[i], Mass, 1));

}

}

}

Within the PhysicEngineProcessor class, we will compute the particle’s position and velocity according to their force diagram that we described earlier. Notice that we do not update the particles in this function. What we do here is storing what need to be updated in the current state. Subsequently, we will update all the particles as a whole in the next Update function.

public void Process()

{

tempVelocities = new List<Vector3d>();

tempPositions = new List<Point3d>();

int particleIndex = 0;

foreach (Particle particle in Particles)

{

if (particle.Status == 0)

{

tempVelocities.Add(Vector3d.Zero);

tempPositions.Add(particle.Position);

particleIndex++;

continue;

}

else

{

// spring force(place holder)

double forceSpring_Z = 0;

double forceSpring_Y = 0;

double forceSpring_X = 0;

// damping force(place holder)

double forceDamping_Z = 0;

double forceDamping_Y = 0;

double forceDamping_X = 0;

// gravity force

double forceGravity = particle.Mass * Gravity;

for (int i = 0; i < Connectivity.Branch(particleIndex).Count; i++)

{

Particle connectedParticle = Particles[Connectivity.Branch(particleIndex)[i]];

// spring force

forceSpring_Z += SpringConstant * (particle.Position.Z - connectedParticle.Position.Z) * (-1);

forceSpring_Y += SpringConstant * (particle.Position.Y - connectedParticle.Position.Y) * (-1);

forceSpring_X += SpringConstant * (particle.Position.X - connectedParticle.Position.X) * (-1);

// damping force

forceDamping_Z += DampingConstant * particle.Velocity.Z * (-1);

forceDamping_Y += DampingConstant * particle.Velocity.Y * (-1);

forceDamping_X += DampingConstant * particle.Velocity.X * (-1);

}

double forceZ = forceSpring_Z + forceDamping_Z + forceGravity;

double forceY = forceSpring_Y + forceDamping_Y;

double forceX = forceSpring_X + forceDamping_X;

Vector3d acceleration = new Vector3d(forceX / particle.Mass, forceY / particle.Mass, forceZ / particle.Mass);

Vector3d currentVelocity = particle.Velocity + acceleration;

Point3d currentPosition = particle.Position + currentVelocity;

tempVelocities.Add(currentVelocity);

tempPositions.Add(currentPosition);

particleIndex++;

}

}

}

Our process function is complete, now we have the updated values for all the particles stored in a temporarily separate list. Let’s update them all at once.

public void Update()

{

int particleIndex = 0;

foreach (Particle particle in Particles)

{

particle.Position = tempPositions[particleIndex];

particle.Velocity = tempVelocities[particleIndex];

particleIndex++;

}

}

Beside from searching the connectivity, when the particles’ positions are updated, we need a function to build the spring back to connect each particle, as such we can visualise their connectivity in the intermediate state.

public List<Line> BuildConnectivity()

{

List<Line> lines = new List<Line>();

for (int i = 0; i < Connectivity.BranchCount; i++)

for (int j = 0; j < Connectivity.Branch(i).Count; j++)

if (Connectivity.Branch(i)[j] > i) // avoid duplicate lines

{

Line line = new Line(Particles[i].Position, Particles[Connectivity.Branch(i)[j]].Position);

lines.Add(line);

}

return lines;

}

Finally, back to the main code area and let’s put everything together to make it works. It is time to instantiate the PhysicEngineProcessor object which will sequentially instantiate the particle objects within the PhysicEngineProcessor constructor.

private void RunScript(List<Curve> curves, List<Point3d> anchorPts, double mass, double gravity, double springConstant, double dampingConstant, bool reset, ref object outPt, ref object outConnectivity, ref object outAnchorIndices)

{

List<Point3d> allParticles;

DataTree<int> connectivity;

Tuple<List<Point3d>, DataTree<int>> searchedConnectivity = SearchConnectivity(curves);

allParticles = searchedConnectivity.Item1;

connectivity = searchedConnectivity.Item2;

List<int> anchorsIndices;

anchorsIndices = SearchAnchorIndices(allParticles, anchorPts);

if (reset || engine == null)

{

particles = allParticles;

for (int i = 0; i < particles.Count; i++) velocities.Add(Vector3d.Zero);

engine = new PhysicEngineProcessor(particles, velocities, anchorsIndices, mass, gravity, springConstant, dampingConstant, connectivity);

}

engine.Process();

engine.Update();

// Outputs-------------------------------------------------------

outPt = allParticles;

outConnectivity = connectivity;

outAnchorIndices = anchorsIndices;

outPositions = engine.GetPositions();

outVelocities = engine.GetVelocities();

outLines = engine.BuildConnectivity();

}

// <Custom additional code>

private PhysicEngineProcessor engine;

List<Point3d> particles = new List<Point3d>();

List<Vector3d> velocities = new List<Vector3d>();

|

|

This kind of concludes the underlying principle of particle system. There are plenty of interesting applications that can be further developed based on particle system logic. One example in the architectural application is planarisation when it comes to panalise a large doubly-curved surface into planar quad surfaces, which is beneficial to fabricate facade panels out of low-stretchable materials, such as timber or glass.